Omega-3-Fettsäuren sind essenzielle Nährstoffe, die für zahlreiche körperliche Prozesse eine entscheidende Rolle spielen. Säugetiere sind auf eine Aufnahme bestimmter Omega-3 Fettsäuren über die Nahrung angewiesen, um lebenswichtige Funktionen aufrechtzuerhalten. Studien zeigen, dass eine zusätzliche Zufuhr über den Grundbedarf hinaus nicht nur gesundheitliche Vorteile bietet, sondern auch ein therapeutisches Potenzial birgt. Während ihr Nutzen in der Humanmedizin verstärkt erforscht wird, wird er bei Tieren oft unterschätzt. Dabei zeigt die Wissenschaft immer deutlicher, dass nahezu jedes Tier von einer gezielten Omega-3-Versorgung profitieren kann.

Fett ist ein essenzieller Grundbaustein

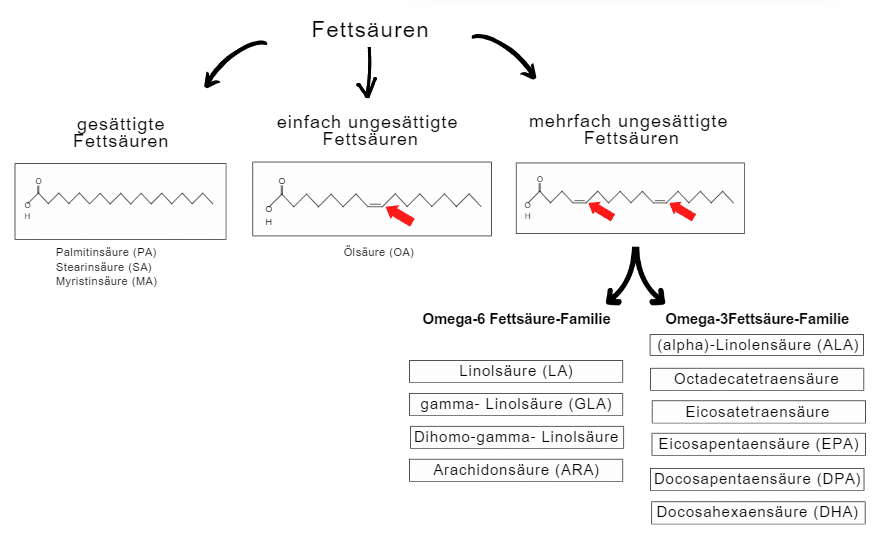

Fettsäuren sind essenzielle Bausteine von Zellmembranen und zentrale Akteure im Stoffwechsel. Sie dienen nicht nur als Energiequelle, sondern sind auch Ausgangsstoffe für eine Vielzahl biologisch aktiver Moleküle. Besonders relevant sind die reaktionsfreudigen mehrfach ungesättigten Fettsäuren, die in Omega-3- und Omega-6-Fettsäuren unterteilt werden. Diese unterscheiden sich in ihrer biochemischen Funktion und beeinflussen zahlreiche physiologische Prozesse.

Omega-3 und Omega-6 –Fettsäuren: Funktionelle Gegenspieler?

Beide, Omega-3- und Omega-6-Fettsäuren, sind für Säugetiere essenziell, müssen also zwingend über die Nahrung aufgenommen werden. Ein Mangel führt zu schwerwiegenden Beeinträchtigungen lebenswichtiger Körperfunktionen und kann zu chronischen Haut- und Fellstörungen, Verdauungsproblemen, Herz-Kreislauf-Erkrankungen, degenerativen Augenerkrankungen und Allergien führen [1]. Aus diesem Grund sollten sie nicht lediglich als ergänzende Nährstoffe betrachtet werden, sondern als entscheidende Bestandteile einer guten Gesundheit.

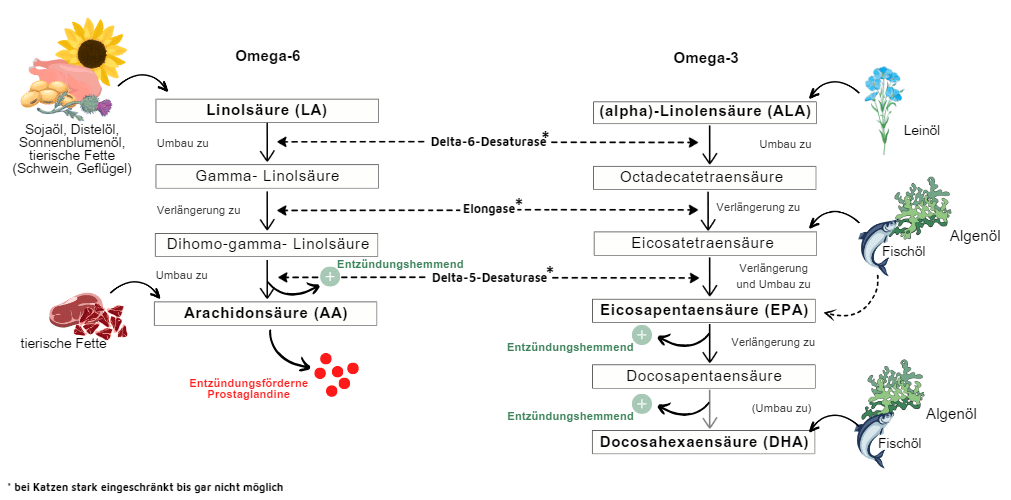

Die wichtigsten Vertreter der Omega-6 Fettsäuren sind Linolsäure (LA) und Arachidonsäure (AA). LA kommt in höheren Mengen in Pflanzenölen, wie Sonnenblumenöl, vor und spielt eine wichtige Rolle bei der Aufrechterhaltung der epidermalen Permeabilitätsbarriere [2-4] und ist ein Vorläufer von AA [5]. AA ist überwiegend in tierischen Fetten vorhanden und wird in entzündungsfördernde Eicosanoiden umgewandelt [6-8]. Damit ist AA ein Bestandteil der Immunregulation.

Die bedeutendsten Omega-3-Fettsäuren sind Alpha-Linolensäure (ALA), Eicosapentaensäure (EPA) und Docosahexaensäure (DHA). ALA ist in pflanzlichen Ölen wie Lein- und Chiaöl enthalten und dient als Vorstufe für EPA und DHA. DHA hate eine Schlüsselrolle in der Entwicklung und Funktion des Nervensystems, insbesondere in Gehirn und Auge [9]. EPA wirkt als eine Art Gegenspieler zu Omega-6 Fettsäuren vornehmlich entzündungshemmend, indem es die Synthese entzündungsfördernder Mediatoren reduziert und stattdessen entzündungsauflösende Resolvine und Protectine produzert [7, 8]. Beide, EPA und DHA, sind in relevanten Mengen ausschließlich in marinen Quellen zu finden.

Ein ausgewogenes Verhältnis zwischen Omega-6- und Omega-3-Fettsäuren ist entscheidend, um entzündliche Prozesse zu regulieren und eine optimale physiologische Funktion aufrechtzuerhalten.

Darum ist eine direkte Fütterung von EPA und DHA effektiver

EPA und DHA sind, anders als ALA, direkt bioverfügbar. ALA muss im Körper erst in EPA und DHA umgewandelt werden [8] (siehe Abbildung 2). Dieser Prozess ist jedoch ineffizient und variiert stark zwischen den Spezies. Hunde und vermutlich auch Pferde können ALA in gewissem Maße zu EPA umwandeln. Ob ihre Leber DPA effizient in DHA konvertieren kann, ist unklar und geschieht, wenn überhaupt, nur in sehr geringem Umfang [10]. Katzen besitzen keine oder nur eine sehr geringe Enzymaktivität für die Umwandlung von ALA in EPA oder DHA und müssen diese daher direkt über die Nahrung aufnehmen [8, 11].

Omega-3/Omega-6 Verhältnis

Im Zusammenhang mit einer gesunden Ernährung wird häufig über ein ausgewogenes Verhältnis zwischen Omega-3 und Omega-6 gesprochen.

Humane Studien wie die Lyon Diet Heart Study und die GISSI-Prevenzione-Studie belegen, dass eine erhöhte Zufuhr von Omega-3-Fettsäuren und damit ein niedrigeres Omega-3 zu Omega-6-Verhältnis mit einer reduzierten Mortalität und verringertem Risiko für Herz-Kreislauf-Erkrankungen einhergeht [12, 13]. Ein hoher Omega-6-Konsum hingegen wird mit einem erhöhten Risiko für Arthritis, Atherosklerose und bestimmte Krebsarten in Verbindung gebracht [14-18]. Auch in Hunden und Katzen haben wir Hinweise, dass sich ein niedrigeres Omega-6/Omega-3-Verhältnis günstig auf die Gesundheit auswirkt [19-21].

Basierend auf den bisherigen Erkenntnissen gibt es keine einheitliche Empfehlung für das optimale Verhältnis von Omega-6 zu Omega-3 für Haustiere. Für Hunde und Katzen wird nach neueren Forschungserkenntnissen aber Verhältnis von unter 10:1 als erstrebenswert angesehen, sofern die Versorgung mit LA sichergestellt ist [22]. Ein entscheidender Faktor ist, dass Omega-6 und Omega-3-Fettsäuren um dieselben Enzyme konkurrieren, die für ihre Umwandlung in bioaktive Metaboliten benötigt werden. Da Omega-6-Fettsäuren bevorzugt von diesen Enzymen in AA umgewandelt werden, kann eine übermäßige Zufuhr nicht nur entzündungsfördernde Prozesse verstärken, sondern auch die enzymatische Umwandlung von ALA in EPA und DHA hemmen [7, 23].

Mit Ausnahme von fleischfressenden Säugetieren wie Katzen, die nur eine Enzymaktivität besitzen, beeinflussen demnach sowohl die relative als auch die absolute Menge an ALA und LA direkt die Umwandlungsrate in EPA, DHA und AA, wie in in-vitro-Studien gezeigt wurde [7, 8].

Darum ist eine Supplementierung von EPA und DHA bei Haustieren i.d.R. sogar notwendig

Die Produktion und Nutzung von Omega-6-reichen Inhaltsstoffen hat in der Tierernährung stark zugenommen. Durch entsprechende Mindestanforderung nach Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) und National Research Council (NRC) besteht in kommerziellen Futtermitteln mit ausreichendem Rohfettgehalt kaum ein Risiko für einen Omega-6-Mangel [22]. Im Gegenteil enthalten viele Futtermittel überhöhte Mengen an Omega-6-Fettsäuren [24]. Auch Pferde bekommen über Raufutter in der Regel ausreichend Omega-6, sodass eine zusätzliche Zufuhr nicht erforderlich ist [25, 26].

EPA und DHA sind im Futter oft unterrepräsentiert

Während Omega-6-Fettsäuren in vielen Tierfuttermitteln reichlich vorhanden sind, sind die langkettigen Omega-3-Fettsäuren EPA und DHA in der Ernährung von Hunden, Katzen und Pferden meist unzureichend enthalten. Der Omega-3-Index, der den prozentualen Anteil von EPA und DHA in den roten Blutkörperchen misst, ist ein anerkannter Marker für den Omega-3-Status [27, 28].

Beim Menschen wird ein Omega-3-Index von ≥ 8 % als optimal für einen präventiven Schutz angesehen, während Werte unter 4 % mit einem erhöhten Krankheitsrisiko assoziiert sind [29]. Während die optimalen Schwellenwerte für Haustiere noch nicht eindeutig definiert sind, liefert der Vergleich mit dem menschlichen Omega-3-Index wertvolle Hinweise darauf, dass auch bei Hunden, Katzen und Pferden ein niedriger EPA- und DHA-Spiegel ein potenzielles Gesundheitsrisiko darstellen könnte. Bisherige Untersuchungen zum Omega-3-Index in Hunden, Katzen und Pferden zeigen zwar eine hohe Variabilität innerhalb der Spezies [41], belegen jedoch gleichzeitig, dass der Anteil an EPA und DHA in den meisten Tieren niedrig ist und häufig weit unter dem angestrebten 8 %-Wert im Menschen liegt (siehe Tabelle 2).

Da eine ausreichende Versorgung mit EPA und DHA über das normale Futter meist nicht gewährleistet werden kann, ist eine gezielte Supplementierung erforderlich, um das Omega-6/Omega-3-Verhältnis zu optimieren und den Omega-3-Index anzuheben.

| Hund | Katze | Pferd |

|---|---|---|

| 2,9 % (n=33) [28] | 2,9 % (n=10) [28] | 0,89 – 1,09% (n= 15) [33] |

| 1,35 –1.37% (n=45) [34] | 1,7 % 1 (n=11) | |

| 1,68% (n=10) [35] | ||

| 1,84 – 1,9 % (n=10) [36] | ||

| 4,7 % 1 (n=42) |

1 bisher unveröffentlichte Daten gemessen durch Omegametrix

Therapeutische Potenziale von EPA und DHA

Neben ihrem präventiven Nutzen gewinnen EPA und DHA zunehmend an Bedeutung als unterstützende Therapie in der Tiermedizin. Die folgende Übersicht zeigt wissenschaftlich untersuchte Einsatzmöglichkeiten bei verschiedenen Tierarten:

| Einsatzbereich | Hunde | Katzen | Pferde | Literatur |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthrose & Gelenke | Empfohlen von der American Animal Hospital Association als nicht-medikamentöse First-Line-Intervention; Studien zeigen signifikante Schmerzlinderung | Ähnliche Wirkung wie bei Hunden, jedoch weniger erforscht. | Wenige Untersuchungen | [1, 10, 26, 30, 32, 37-116] |

| Herz-Kreislauf-System | Hinweise auf reduzierte Herzrhythmusstörungen, geringeren Muskelabbau und erhöhte Überlebensrate bei Herzinsuffizienz | Keine spezifischen Studien zu Omega-3 und Herzerkrankungen | Potenzielle Vorteile durch reduzierte Triglyceridwerte, jedoch fehlen spezifische Studien | [117-121] |

| Haut & Fell | Reduzierter Medikamentenbedarf bei atopischer Dermatitis | Verbesserung bei miliarer Dermatitis nach 6 Wochen | Hinweise auf positive Effekte, aber keine spezifischen Studien | [122-127] |

| Gehirn & kognitive Funktionen | DHA-Supplementation als Zusatztherapie bei Epilepsie; mögliche Prävention kognitiven Verfalls | Keine spezifischen Studien | Keine spezifischen Studien | [128-131] |

| Weitere Einsatzgebiete | Unterstützt Augengesundheit, Behandlung von Hyperlipidämie und potenzieller Schutz der Nierenfunktion | Erste Hinweise auf entzündungshemmende Wirkung bei Parodontalerkrankungen | Potenzielle Verbesserungen bei Atemwegserkrankungen | [43, 132-138] |

Sicherheit und Nebenwirkungen

Omega-3-Fettsäuren gelten als sicher und gut verträglich für Hunde, Katzen und Pferde, können jedoch in hohen Dosen die Blutgerinnung beeinflussen und die Thrombozytenfunktion beeinträchtigen [30, 31]. Es gibt zudem Hinweise auf eine mögliche Beeinträchtigung der Immunfunktion sowie Veränderungen im Glukose- und Lipidstoffwechsel [1] . Da mehrfach ungesättigte Fettsäuren anfällig für Lipidperoxidation sind, wird eine ausreichende Versorgung mit Antioxidantien, insbesondere Vitamin E, empfohlen. Wechselwirkungen mit Medikamenten wie Nicht-steroidalen Entzündungshemmern (z. B. Carprofen) oder Thrombozytenaggregationshemmern (z. B. Clopidogrel) könnten die Blutstillung beeinträchtigen und sollten tierärztlich abgeklärt werden [32].

Insgesamt überwiegen die gesundheitlichen Vorteile einer gezielten Omega-3-Supplementierung deutlich, sofern sie bedarfsgerecht dosiert und individuell angepasst wird.

Fazit

Omega-3-Fettsäuren sind für viele physiologische Prozesse unverzichtbar. Angesichts der modernen Ernährungsbedingungen ist eine Supplementierung oft sinnvoll, um ein gesundes Omega-6-zu-Omega-3-Verhältnis zu erreichen. Wissenschaftliche Studien zeigen, dass Tiere mit entzündlichen Erkrankungen, Herz-Kreislauf-Problemen oder Hautproblemen besonders profitieren können. Weitere Forschung ist notwendig, um das Potenzial, sowie Sicherheit und Nebenwirkungen weiter zu beleuchten.

Artikel von Dr. rer. nat. Jessica Farger

foten, die tierische Schwester von NORSAN und spezialisiert sich auf hochwertige Omega-3-Produkte für Tiere. Mit einem Fokus auf natürliche Inhaltsstoffe und wissenschaftlich fundierte Rezepturen entwickelt foten Produkte, die gezielt die Gesundheit und das Wohlbefinden unserer Vierbeiner unterstützen. Dabei legt foten besonderen Wert auf Qualität, Transparenz und Umweltfreundlichkeit.

Produkte für Ihre Vierbeiner

Quellen:

1. Kaur, H., et al., Role of omega-3 fatty acids in canine health: a review. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 2020. 9(3): p. 2283-2293.

2. Burr, G.O. and M.M. Burr, A new deficiency disease produced by the rigid exclusion of fat from the diet. Journal of biological chemistry, 1929. 82(2): p. 345-367.

3. Burr, G.O. and M.M. Burr, On the nature and role of the fatty acids essential in nutrition. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1930. 86(2): p. 587-621.

4. Wertz, P. Epidermal lipids. in Seminars in dermatology. 1992.

5. Whelan, J. and K. Fritsche, Linoleic acid. Adv. Nutr. 4, 311–312. 2013.

6. Scott, D. What’s new on canine dermatology. in Proceedings of 12th Annual Congress of European Society of Veterinary Dermatology, Barcelona, Spain. 1995.

7. Liou, Y.A., et al., Decreasing Linoleic Acid with Constant α-Linolenic Acid in Dietary Fats Increases (n-3) Eicosapentaenoic Acid in Plasma Phospholipids in Healthy Men1. The Journal of nutrition, 2007. 137(4): p. 945-952.

8. Goyens, P.L., et al., Conversion of α-linolenic acid in humans is influenced by the absolute amounts of α-linolenic acid and linoleic acid in the diet and not by their ratio. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2006. 84(1): p. 44-53.

9. Tocher, D.R., et al., Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, EPA and DHA: Bridging the gap between supply and demand. Nutrients, 2019. 11(1): p. 89.

10. Dunbar, B.L., K.E. Bigley, and J.E. Bauer, Early and sustained enrichment of serum n‐3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in dogs fed a flaxseed supplemented diet. Lipids, 2010. 45(1): p. 1-10.

11. Rivers, J., A. Sinclair, and M. Crawford, Inability of the cat to desaturate essential fatty acids. Nature, 1975. 258(5531): p. 171-173.

12. De Lorgeril, M., et al., Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. The lancet, 1994. 343(8911): p. 1454-1459.

13. Investigators, G.-P., Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. The Lancet, 1999. 354(9177): p. 447-455.

14. Libby, P., P.M. Ridker, and A. Maseri, Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation, 2002. 105(9): p. 1135-1143.

15. de Visser, K.E. and L.M. Coussens, The inflammatory tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer development. Infection and Inflammation: Impacts on Oncogenesis, 2006. 13: p. 118-137.

16. Murdoch, J.R. and C.M. Lloyd, Chronic inflammation and asthma. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, 2010. 690(1-2): p. 24-39.

17. Sorriento, D. and G. Iaccarino, Inflammation and cardiovascular diseases: the most recent findings. 2019, MDPI. p. 3879.

18. Tsalamandris, S., et al., The role of inflammation in diabetes: current concepts and future perspectives. European cardiology review, 2019. 14(1): p. 50.

19. Vaughn, D.M., et al., Evaluation of effects of dietary n‐6 to n‐3 fatty acid ratios on leukotriene B synthesis in dog skin and neutrophils. Veterinary Dermatology, 1994. 5(4): p. 163-173.

20. Park, H.J., et al., Dietary fish oil and flaxseed oil suppress inflammation and immunity in cats. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology, 2011. 141(3-4): p. 301-306.

21. Hall, J.A., et al., Increased dietary long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids alter serum fatty acid concentrations and lower risk of urine stone formation in cats. PLoS One, 2017. 12(10): p. e0187133.

22. Burron, S., et al., The balance of n-6 and n-3 fatty acids in canine, feline and equine nutrition: exploring sources and the significance of alpha-linolenic acid. Journal of Animal Science, 2024: p. skae143.

23. Zivkovic, A.M., et al., Dietary omega-3 fatty acids aid in the modulation of inflammation and metabolic health. California agriculture, 2011. 65(3): p. 106.

24. Department, A.O.o.t.U.N.F., The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2000. Vol. 3. 2000: Food & Agriculture Org.

25. Kearns, R.J., et al., Effect of age, breed and dietary omega-6 (n-6): omega-3 (n-3) fatty acid ratio on immune function, eicosanoid production, and lipid peroxidation in young and aged dogs. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology, 1999. 69(2-4): p. 165-183.

26. LeBlanc, C.J., et al., Effect of dietary fish oil and vitamin E supplementation on hematologic and serum biochemical analytes and oxidative status in young dogs. Veterinary Therapeutics, 2005. 6(4): p. 325.

27. Harris, W.S. and C. Von Schacky, The Omega-3 Index: a new risk factor for death from coronary heart disease? Preventive medicine, 2004. 39(1): p. 212-220.

28. Harris, W.S., et al., Derivation of the omega-3 index from EPA and DHA analysis of dried blood spots from dogs and cats. Veterinary Sciences, 2022. 10(1): p. 13.

29. Harris, W.S., The omega-3 index as a risk factor for coronary heart disease. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2008. 87(6): p. 1997S-2002S.

30. Hall, J.A., Potential adverse effects of long-term consumption of (n-3) fatty acids. The Compendium on continuing education for the practicing veterinarian (USA), 1996.

31. Nabavi, S.F., et al., Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cancer: lessons learned from clinical trials. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 2015. 34: p. 359-380.

32. Lenox, C. and J. Bauer, Potential adverse effects of omega‐3 fatty acids in dogs and cats. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2013. 27(2): p. 217-226.

33. Pearson, G., et al., Dose-Dependent Increase in Whole Blood Omega-3 Fatty Acid Concentration in Horses Receiving a Marine-Based Fatty-Acid Supplement. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 2022. 108: p. 103781.

34. Lindqvist, H., et al., Comparison of fish, krill and flaxseed as omega-3 sources to increase the omega-3 index in dogs. Veterinary Sciences, 2023. 10(2): p. 162.

35. Dominguez, T.E., K. Kaur, and L. Burri, Enhanced omega‐3 index after long‐versus short‐chain omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation in dogs. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 2021. 7(2): p. 370-377.

36. Burri, L., K. Heggen, and A.B. Storsve, Higher omega-3 index after dietary inclusion of omega-3 phospholipids versus omega-3 triglycerides in Alaskan Huskies. Veterinary World, 2020. 13(6): p. 1167.

37. Lascelles, B., et al., Evaluation of a therapeutic diet for feline degenerative joint disease. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2010. 24(3): p. 487-495.

38. Barbeau-Gregoire, M., et al., A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of enriched therapeutic diets and nutraceuticals in canine and feline osteoarthritis. International journal of molecular sciences, 2022. 23(18): p. 10384.

39. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12035-018-1029-5.

41. Loef, M., et al., Fatty acids and osteoarthritis: different types, different effects. Joint Bone Spine, 2019. 86(4): p. 451-458.

42. McNiel, E.A., et al., Platelet function in dogs treated for lymphoma and hemangiosarcoma and supplemented with dietary n‐3 fatty acids. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 1999. 13(6): p. 574-580.

43. Ogilvie, G.K., et al., Effect of fish oil, arginine, and doxorubicin chemotherapy on remission and survival time for dogs with lymphoma: a double‐blind, randomized placebo‐controlled study. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society, 2000. 88(8): p. 1916-1928.

44. Laflamme, D., H. Xu, and G. Long, Effect of diets differing in fat content on chronic diarrhea in cats. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2011. 25(2): p. 230-235.

45. Soong, D., et al., Hydroxy fatty acids in human diarrhea. Gastroenterology, 1972. 63(5): p. 748-757.

46. Kirby, N.A., S.L. Hester, and J.E. Bauer, Dietary fats and the skin and coat of dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2007. 230(11): p. 1641-1644.

47. Harris, W.S., S. Silveira, and C.A. Dujovne, The combined effects of N-3 fatty acids and aspirin on hemostatic parameters in man. Thrombosis research, 1990. 57(4): p. 517-526.

48. Guillot, N., et al., Increasing intakes of the long‐chain ω‐3 docosahexaenoic acid: effects on platelet functions and redox status in healthy men. The FASEB Journal, 2009. 23(9): p. 2909-2916.

49. Boudreaux, M.K., et al., The effects of varying dietary n-6 to n-3 fatty acid ratios on platelet reactivity, coagulation screening assays, and antithrombin III activity in dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 1997. 33(3): p. 235-243.

50. Thorngren, M. and A. Gustafson, Effects of 11-week increase in dietary eicosapentaenoic acid on bleeding time, lipids, and platelet aggregation. The Lancet, 1981. 318(8257): p. 1190-1193.

51. Lien, E.L., Toxicology and safety of DHA. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes and essential fatty acids, 2009. 81(2-3): p. 125-132.

52. Zainal, Z., et al., Relative efficacies of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in reducing expression of key proteins in a model system for studying osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage, 2009. 17(7): p. 896-905.

53. Huang, M.-j., et al., Enhancement of the synthesis of n-3 PUFAs in fat-1 transgenic mice inhibits mTORC1 signalling and delays surgically induced osteoarthritis in comparison with wild-type mice. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 2014. 73(9): p. 1719-1727.

54. Lu, B., et al., Dietary fat intake and radiographic progression of knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis care & research, 2017. 69(3): p. 368-375.

55. Curtis, C.L., et al., Pathologic indicators of degradation and inflammation in human osteoarthritic cartilage are abrogated by exposure to n‐3 fatty acids. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, 2002. 46(6): p. 1544-1553.

56. Shen, C.L., et al., Decreased production of inflammatory mediators in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes by conjugated linoleic acids. Lipids, 2004. 39(2): p. 161-166.

57. Bagga, D., et al., Differential effects of prostaglandin derived from ω-6 and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on COX-2 expression and IL-6 secretion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2003. 100(4): p. 1751-1756.

58. Simopoulos, A.P., Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. Journal of the American College of nutrition, 2002. 21(6): p. 495-505.

59. Gil, A., Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory diseases. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy, 2002. 56(8): p. 388-396.

60. Calder, P.C., Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and immunity. Lipids, 2001. 36(9): p. 1007-1024.

61. Browning, L.M., n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation and obesity-related disease. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 2003. 62(2): p. 447-453.

62. De Caterina, R., et al., n-3 fatty acids and renal diseases. American journal of kidney diseases, 1994. 24(3): p. 397-415.

63. Mori, T.A. and L.J. Beilin, Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammation. Current atherosclerosis reports, 2004. 6(6): p. 461-467.

64. Johnston, S.A., Osteoarthritis: joint anatomy, physiology, and pathobiology. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 1997. 27(4): p. 699-723.

65. Hall, J.A., et al., The (n-3) fatty acid dose, independent of the (n-6) to (n-3) fatty acid ratio, affects the plasma fatty acid profile of normal dogs. The Journal of nutrition, 2006. 136(9): p. 2338-2344.

66. Adler, N., A. Schoeniger, and H. Fuhrmann, Polyunsaturated fatty acids influence inflammatory markers in a cellular model for canine osteoarthritis. Journal of animal physiology and animal nutrition, 2018. 102(2): p. e623-e632.

67. Da Silva, E., et al., Omega-3 fatty acids differentially modulate enzymatic anti-oxidant systems in skeletal muscle cells. Cell Stress and Chaperones, 2016. 21: p. 87-95.

68. Garrel, C., et al., Omega-3 fatty acids enhance mitochondrial superoxide dismutase activity in rat organs during post-natal development. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology, 2012. 44(1): p. 123-131.

69. Zararsiz, I., et al., Protective effects of omega-3 essential fatty acids against formaldehyde-induced cerebellar damage in rats. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 2011. 27(6): p. 489-495.

70. Heshmati, J., et al., Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation and oxidative stress parameters: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Pharmacological research, 2019. 149: p. 104462.

71. Gruenwald, J., et al., Effect of glucosamine sulfate with or without omega-3 fatty acids in patients with osteoarthritis. Advances in therapy, 2009. 26: p. 858-871.

72. Jacquet, A., et al., Phytalgic®, a food supplement, vs placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis research & therapy, 2009. 11: p. 1-9.

73. Zapata, A. and R. Fernández-Parra, Management of Osteoarthritis and Joint Support Using Feed Supplements: A Scoping Review of Undenatured Type II Collagen and Boswellia serrata. Animals, 2023. 13(5): p. 870.

74. Hesslink, R., et al., Cetylated fatty acids improve knee function in patients with osteoarthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology, 2002. 29(8): p. 1708-1712.

75. Kraemer, W.J., et al., Effect of a cetylated fatty acid topical cream on functional mobility and quality of life of patients with osteoarthritis. The Journal of rheumatology, 2004. 31(4): p. 767-774.

76. Hill, C.L., et al., Fish oil in knee osteoarthritis: a randomised clinical trial of low dose versus high dose. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 2016. 75(1): p. 23-29.

77. Kremer, J.M., Clinical studies of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America, 1991. 17(2): p. 391-402.

78. Au, K.K., et al., Comparison of short‐and long‐term function and radiographic osteoarthrosis in dogs after postoperative physical rehabilitation and tibial plateau leveling osteotomy or lateral fabellar suture stabilization. Veterinary Surgery, 2010. 39(2): p. 173-180.

79. Nelson, S.A., et al., Long‐term functional outcome of tibial plateau leveling osteotomy versus extracapsular repair in a heterogeneous population of dogs. Veterinary Surgery, 2013. 42(1): p. 38-50.

80. Robinson, D.A., et al., The effect of tibial plateau angle on ground reaction forces 4–17 months after tibial plateau leveling osteotomy in Labrador Retrievers. Veterinary Surgery, 2006. 35(3): p. 294-299.

81. Bauer, J.E., Therapeutic use of fish oils in companion animals. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2011. 239(11): p. 1441-1451.

82. Fritsch, D.A., et al., A multicenter study of the effect of dietary supplementation with fish oil omega-3 fatty acids on carprofen dosage in dogs with osteoarthritis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2010. 236(5): p. 535-539.

83. Roush, J.K., et al., Evaluation of the effects of dietary supplementation with fish oil omega-3 fatty acids on weight bearing in dogs with osteoarthritis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2010. 236(1): p. 67-73.

84. Bibus, D. and P. Stitt, Metabolism of -Linolenic Acid from Flaxseed in Dogs. World review of nutrition and dietetics, 1998: p. 186-198.

85. Stamey, J., et al., Use of algae or algal oil rich in n-3 fatty acids as a feed supplement for dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science, 2012. 95(9): p. 5269-5275.

86. Kremer, J., et al., Effects of manipulation of dietary fatty acids on clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet, 1985. 325(8422): p. 184-187.

87. Salomon, P., A.A. Kornbluth, and H.D. Janowitz, Treatment of ulcerative colitis with fish oil n-3-ω-fatty acid: an open trial. Journal of clinical gastroenterology, 1990. 12(2): p. 157-161.

88. Almallah, Y., et al., Distal procto-colitis and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: the mechanism (s) of natural cytotoxicity inhibition. European journal of clinical investigation, 2000. 30(1): p. 58-65.

89. Bauer, J.E., B.L. Dunbar, and K.E. Bigley, Dietary flaxseed in dogs results in differential transport and metabolism of (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids. The Journal of nutrition, 1998. 128(12): p. 2641S-2644S.

90. Brenna, J.T., et al., α-Linolenic acid supplementation and conversion to n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in humans. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes and essential fatty acids, 2009. 80(2-3): p. 85-91.

91. Waldron, M.K., S.S. Hannah, and J.E. Bauer, Plasma phospholipid fatty acid and ex vivo neutrophil responses are differentially altered in dogs fed fish-and linseed-oil containing diets at the same n-6: n-3 fatty acid ratio. Lipids, 2012. 47: p. 425-434.

92. Bays, H.E., Safety considerations with omega-3 fatty acid therapy. The American journal of cardiology, 2007. 99(6): p. S35-S43.

93. Mehler, S.J., et al., A prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on the clinical signs and erythrocyte membrane polyunsaturated fatty acid concentrations in dogs with osteoarthritis. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 2016. 109: p. 1-7.

94. Mueller, R.S., et al., Plasma and skin concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids before and after supplementation with n-3 fatty acids in dogs with atopic dermatitis. American journal of veterinary research, 2005. 66(5): p. 868-873.

95. Baltzer, W.I., et al., Evaluation of the clinical effects of diet and physical rehabilitation in dogs following tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2018. 252(6): p. 686-700.

96. Verpaalen, V.D., et al., Assessment of the effects of diet and physical rehabilitation on radiographic findings and markers of synovial inflammation in dogs following tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2018. 252(6): p. 701-709.

97. Hansen, R.A., et al., Fish oil decreases matrix metalloproteinases in knee synovia of dogs with inflammatory joint disease. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry, 2008. 19(2): p. 101-108.

98. Miao, H., et al., Stearic acid induces proinflammatory cytokine production partly through activation of lactate-HIF1α pathway in chondrocytes. Scientific reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 1-12.

99. Deng, W., et al., Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation for patients with osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 2023. 18(1): p. 1-11.

100. Bahamondes, M.A., C. Valdés, and G. Moncada, Effect of omega-3 on painful symptoms of patients with osteoarthritis of the synovial joints: systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology, 2021. 132(3): p. 297-306.

101. Barbeau-Grégoire, M., et al., A 2022 Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Enriched Therapeutic Diets and Nutraceuticals in Canine and Feline Osteoarthritis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022. 23(18): p. 10384.

102. Kolanowski, W., Omega-3 LC PUFA contents and oxidative stability of encapsulated fish oil dietary supplements. International journal of food properties, 2010. 13(3): p. 498-511.

103. Albina, J., P. Gladden, and W. Walsh, Detrimental Effects of an ω‐3 Fatty Acid‐Enriched Diet on Wound Healing. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 1993. 17(6): p. 519-521.

104. Otranto, M., A.P. Do Nascimento, and A. Monte‐Alto‐Costa, Effects of supplementation with different edible oils on cutaneous wound healing. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 2010. 18(6): p. 629-636.

105. Gercek, A., et al., Effects of parenteral fish‐oil emulsion (Omegaven) on cutaneous wound healing in rats treated with dexamethasone. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 2007. 31(3): p. 161-166.

106. Corbee, R., et al., Inflammation and wound healing in cats with chronic gingivitis/stomatitis after extraction of all premolars and molars were not affected by feeding of two diets with different omega‐6/omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratios. Journal of animal physiology and animal nutrition, 2012. 96(4): p. 671-680.

107. Mooney, M., et al., Evaluation of the effects of omega-3 fatty acid-containing diets on the inflammatory stage of wound healing in dogs. American journal of veterinary research, 1998. 59(7): p. 859-863.

108. Scardino, M., The effects of omega-3 fatty acid diet enrichment on wound healing. Vet Dermatol, 1999. 10: p. 283-290.

109. Wander, R.C., et al., The ratio of dietary (n-6) to (n-3) fatty acids influences immune system function, eicosanoid metabolism, lipid peroxidation and vitamin E status in aged dogs. The Journal of nutrition, 1997. 127(6): p. 1198-1205.

110. LeBlanc, C.J., et al., Effects of dietary fish oil and vitamin E supplementation on canine lymphocyte proliferation evaluated using a flow cytometric technique. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology, 2007. 119(3-4): p. 180-188.

111. Chowdhury, K., et al., Studies on the fatty acid composition of edible oil. Bangladesh Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research, 2007. 42(3): p. 311-316.

112. Ackman, R., W. Ratnayake, and E. Macpherson, EPA and DHA contents of encapsulated fish oil products. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 1989. 66(8): p. 1162-1164.

113. Harris, W.S., The omega-6/omega-3 ratio and cardiovascular disease risk: uses and abuses. Current atherosclerosis reports, 2006. 8(6): p. 453-459.

114. Stanley, J.C., et al., UK Food Standards Agency Workshop Report: the effects of the dietary n-6: n-3 fatty acid ratio on cardiovascular health. British Journal of Nutrition, 2007. 98(6): p. 1305-1310.

115. Blonk, M.C., et al., Dose-response effects of fish-oil supplementation in healthy volunteers. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 1990. 52(1): p. 120-127.

116. Filburn, C.R. and D. Griffin, Canine plasma and erythrocyte response to a docosahexaenoic acid-enriched supplement: characterization and potential benefits. Veterinary therapeutics: research in applied veterinary medicine, 2005. 6(1): p. 29-42.

117. Smith, C.E., et al., Omega‐3 fatty acids in Boxer dogs with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2007. 21(2): p. 265-273.

118. Sakabe, M., et al., Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids prevent atrial fibrillation associated with heart failure but not atrial tachycardia remodeling. Circulation, 2007. 116(19): p. 2101-2109.

119. Slupe, J., L. Freeman, and J. Rush, Association of body weight and body condition with survival in dogs with heart failure. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2008. 22(3): p. 561-565.

120. Freeman, L.M., Beneficial effects of omega‐3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 2010. 51(9): p. 462-470.

121. O’Connor, C., L. Lawrence, and S. Hayes, Dietary fish oil supplementation affects serum fatty acid concentrations in horses. Journal of animal science, 2007. 85(9): p. 2183-2189.

122. Müller, M., et al., Evaluation of cyclosporine-sparing effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis. The Veterinary Journal, 2016. 210: p. 77-81.

123. Saevik, B.K., et al., A randomized, controlled study to evaluate the steroid sparing effect of essential fatty acid supplementation in the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis. Veterinary dermatology, 2004. 15(3): p. 137-145.

124. Schäfer, L. and N. Thom, A placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study evaluating the effect of orally administered polyunsaturated fatty acids on the oclacitinib dose for atopic dogs. Veterinary Dermatology, 2024.

125. Lechowski, R., E. Sawosz, and W. Klucińskl, The effect of the addition of oil preparation with increased content of n‐3 fatty acids on serum lipid profile and clinical condition of cats with miliary dermatitis. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A, 1998. 45(1‐10): p. 417-424.

126. Hall, J.A., R.J. Van Saun, and R.C. Wander, Dietary (n‐3) fatty acids from Menhaden fish oil alter plasma fatty acids and leukotriene B synthesis in healthy horses. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2004. 18(6): p. 871-879.

127. O’Neill, W., S. McKee, and A.F. Clarke, Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) supplementation associated with reduced skin test lesional area in horses with Culicoides hypersensitivity. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research, 2002. 66(4): p. 272.

128. Pourmasoumi, M., et al., Association of omega-3 fatty acid and epileptic seizure in epileptic patients: a systematic review. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2018. 9(1): p. 36.

129. Yonezawa, T., et al., Effects of high-dose docosahexaenoic acid supplementation as an add-on therapy for canine idiopathic epilepsy: A pilot study. Open Veterinary Journal, 2023. 13(7): p. 942-947.

130. Pan, Y., et al., Cognitive enhancement in old dogs from dietary supplementation with a nutrient blend containing arginine, antioxidants, B vitamins and fish oil. British journal of nutrition, 2018. 119(3): p. 349-358.

131. Zicker, S.C., et al., Evaluation of cognitive learning, memory, psychomotor, immunologic, and retinal functions in healthy puppies fed foods fortified with docosahexaenoic acid–rich fish oil from 8 to 52 weeks of age. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2012. 241(5): p. 583-594.

132. Silva, D.A., et al., Oral omega 3 in different proportions of EPA, DHA, and antioxidants as adjuvant in treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in dogs. Arquivos Brasileiros de Oftalmologia, 2018. 81(5): p. 421-428.

133. Bauer, J.E., Evaluation and dietary considerations in idiopathic hyperlipidemia in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 1995. 206(11): p. 1684-1688.

134. Schenck, P.A., et al., Disorders of calcium: hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia. Fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base disorders in small animal practice, 2006. 4: p. 120-94.

135. Brown, S.A., et al., Beneficial effects of chronic administration of dietary ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in dogs with renal insufficiency. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 1998. 131(5): p. 447-455.

136. Asif, M., The impact of dietary fat and polyunsaturated fatty acids on chronic renal diseases. Current Science Perspectives, 2015. 1(2): p. 51-61.

137. Neprelyuk, O.A., O.L. Irza, and M.A. Kriventsov, Omega-3 fatty acids as a treatment option in periodontitis: Systematic review of preclinical studies. Nutrition and Health, 2024. 30(4): p. 671-685.138. Nogradi, N., et al., Omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation provides an additional benefit to a low‐dust diet in the management of horses with chronic lower airway inflammatory disease. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2015. 29(1): p. 299-306.